Belgium gained governing control over Ruanda /Urundi,

now renamed Rwanda and Burundi, in 1918 under the Treaty of Versailles.

Germany, defeated in World War I, lost its control of German East Africa, the

western part of which was given to Belgium. Neither Germany nor Belgium had

much knowledge or insight about the people living there but, because the

territory bordered on Belgian Congo and none of the other victorious Allies

particularly wanted it, Ruanda/Urundi passed to Belgium.

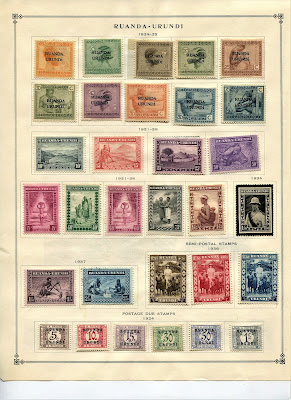

Not until 1924 was the first postage issued, all

repurposed stamps of the 1923 Belgian Congo series. These overprints continued

in use until 1931, Scott numbers 6 through 36. For some reason, a lower case

“i” is used in the spelling of “URUNDi.

Scott numbers 1 through 5 no longer appear in the Scott’s

Ruanda /Urundi listings. Being wartime occupation stamps, they were shifted to

Scott’s section for German East Africa and identified as n25 – n29.

In precolonial times the

population of Ruanda/Urundi was comprised mainly of the Bantu-speaking Hutu and

Tutsi tribes (the latter being known to Europeans as Batutsi or Watusi). Society

was organized in a feudal system with the Tutsis as chiefs and Hutus as

workers. The lines between the two groups were porous. People could intermarry

and move back-and-forth socially. Those identifying as Hutu outnumbered the

Tutsi six to one. An additional very small minority identified as Twa, a

marginalized pygmy people.

The Germans and Belgians

turned this traditional arrangement into a rigid race-based class system, using

now discredited European theories of race as justification. Tribal identity was

fixed at birth and remained that way throughout life. Moreover, the Belgians

favored the Tutsi over the Hutus, giving them European-style education and

privileges of power. In 1926, the Belgians introduced separate ethnic identity

cards (indangamuntu) for the Tutsi and Hutu to carry, a policy that

helped the Tutsi enforce Belgian control.

This hardline

classification provoked the tensions that led, in great part, to genocide in

the 1990s. During and after the genocide the cards were used to identify

victims; most were Tutsi. The card, originally signifying entitlement to power,

became a passport to death.

A Tutsi identified.

Does anything in the

early stamps of Rwanda/Urundi, I wonder, predict the ensuing horrors of the genocide?

In 1931 Belgium issued the first stamps with “Ruanda/Urundi” inscribed. The artwork

features native people in a variety of settings. Although the tribal identity

of the subjects is not mentioned on these stamps, Tutsis likely posed for the

original artwork (or were imagined by the artists). The resulting images

conform to the European racial biases of the time – tall body, narrow nose,

slender face, etc. Belgium chose their favored subjects for colonial stamp

designs.

Scott # 54 brown, 52 gray, and 53 brown violet

Otherwise, I find no

philatelic hints about the underlying conditions that led to genocide.

The late 1990s the genocide

eventually spent its anger and, in more recent years, Tutsis and Hutus are

learning to live together again.

Census: in BB spaces 31, on supplement pages 38. Catalog values for mint and used stamps are basically the same.

No comments:

Post a Comment