Most of us stamp collectors find our hobby satisfying

at many levels, down to the reptilian core of our brains. Who among us has not

felt our heart racing or temperature rising upon finding the right stamp? But

beyond rewarding our lizard-like cravings, more cerebral satisfactions also

accrue from our pet obsession.

Many of us look for stamps with historical relevance.

Peru’s stamps, especially those with overprints, oblige nicely. That’s not

surprising. Peru’s first inhabitants settled some 15,000 years ago.

Conquistador Francisco Pizarro and the first Europeans arrived in 1532. The University

of San Marcos (Lima) was founded in 1551, a century before Harvard was

chartered. Eventually Peru became the seat of the South American Spanish

Empire. So, there is plenty of history to inspire Peru’s stamp designs.

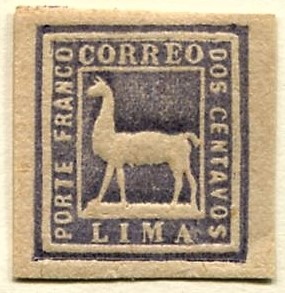

Peru’s earliest stamps (1857-94) are devoid of human

images -- an unusual omission -- unless you count the barely discernable

passengers on the steamship’s deck (Scott #s 1 and 2). Instead, they feature

the Inca sun god, wildlife, and Peru’s coat of arms – populated by a vicuna, a

quinine yielding tree, and a cornucopia of gold coins.

The coat of arms is often difficult to

discern because of heavy cancellations and indistinct embossing made by the

French "Lecoq" machine.

Peru’s name did not appear on its postage until 1866.

If you

like baroque puzzles, try sorting out the history behind Peru’s late 19th

century overprints. Sometimes applied three deep, they reflect Peru’s history

between 1874 and 1894 as it actually was happening. Peru’s

economic and political upheavals, an invasions by Chile, and the death of a

hero/president – all are documented philatelically by a jumble overprints.

These appear entirely on Peru’s 1874 issue, seven stamps ranging in value from

1 centavo to 1 sol. Forgeries and special combinations of overprints concocted

to please collectors, but never issued, only partly muddle the story that

unfolds.

Overprints three deep, unissued

By 1880, Peru’s paper money was practically worthless on the international market, so the 1874 stamps were overprinted with “Universal Postal Union,” “plata” and “Peru” in an oval. In effect surcharged, these stamp required being purchased in silver (plata) and were for international mail only. Domestic postage could still be purchased with paper money.

The Chileans

had been warring with Peruvians since 1879. When in 1881 Chile gained control

of Lima and took over the government, including the post office, “Peru” was

changed to “Lima” at the bottom of the overprint. This hostility, known as the

War of the Pacific, was bloody. Both Peru and Bolivia suffered major losses,

including Bolivia’s access to the Pacific Ocean.

For further affrontery, in 1881 Chile’s

postal authorities cattle-branded their own coat of arms on Peru’s 1874 issue.

Some of these were further overprinted with UPU horseshoes for international

use (see last supplement page).

But the Chileans were dispatched from Lima in 1883, thus requiring new overprints, this time restoring “Peru” in a triangle on, of course, the ever-durable 1974 series.

Further, the remaining stamps

with the “Lima” that the Chileans emblazed required an additional overprint to

celebrate Peru’s regaining control.

Scott # 81, rose

At the same time, new UPU horseshoe overprints for international mail were required and issued both with and without the victorious Peruvian triangle.

Largely to promote philatelic sales, Peru produced the “correos Lima” overprints in 1884. Only the five centavos denomination was issued, reserving the one and two centavo sun-god-upon-sun-god stamps for curiosity collectors (see first supplement page). BB has space for the five centavos only.

Perhaps running short of postage for international use, Peru reissued the plata-Lima ovals in 1889 with the larger of the two plata fonts. Peru’s paper currency was still suffering from devaluation.

Then in 1894

the trustworthy 1874

series was pressed into service for a final time to mourn the death of

President Remigio Morales Bermudez, whose grandson that he never saw also

became Peru’s president. This last overprint is unique in philately – almost a

funerary death mask that appears both alone and with the UPU horseshoes.

Scott #120, rose

While the used and abused 1874 series drops out of sight at this point, other overprints and the upheavals associated with them continue in Peru’s philatelic history. As soon as 1895 vermilion surcharged stamps prepared by revolutionaries emerged in the Tumbus region of northern Peru.

Peru’s overprints are like

baroque puzzles; the one shown below has 30 strange interlocking pieces. The overprints

interlock, too. I’m still working on the puzzle and the overprints. And I have yet

to start on the local provisional issues that cropped up during the Peru-Chile war

– defiant overprints devised in localities that Chile had not conquered.

Census: 314 in BB spaces, 14

tip-ins, 122 on supplement pages (Note: Some stamps in the supplement pages are

mounted sideways to facilitate reading the postmarks.)

(1) An often-forged stamp, see https://stampforgeries.blogspot.com/search?q=peru

2) This post, in part, is informed by: A. L. de la Torre Bueno “The Regular Issues of Peru” The Postage Stamp, Vol 11, No 11, December 14, 1912, p. 123. Originally published in Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News.

.jpg)

A VERY helpful post, many thanks. Thanks for the detail on the overprints. Very useful. Lima is an amazing city, who knew multi-hundred year old churches could survive their earthquakes built on sticks and mud. Great stuff.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Roy. Overprints always present interesting challenges, especially because so many are forgeries, as is the case with Peru. But, then, even the existence of many fakes indicates that collectors care about the history.

ReplyDeleteLima's (and Cusco's) old churches are not only surprisingly sturdy, but also spectacular examples of Andean baroque architecture.